Building Your First Micro-Satellite Mock-Up at Future Space Pioneers Academy

At Future Space Pioneers Academy, we’re all about making space education accessible and exciting for Michigan students. Our 2026-2027 cohort program includes a comprehensive low-cost hardware kit provided to every participant, enabling teams to assemble a functional mock-up of a 1U CubeSat (10x10x10 cm frame). This kit uses affordable, off-the-shelf components to simulate real satellite operations, teaching core STEM skills without breaking the bank. Priced at under $500 per kit (based on bulk sourcing from sites like Amazon, Adafruit, and SparkFun), it democratizes space tech learning. Below, we break down the key components, the assembly process, lessons learned, and how this scales to space-worthy hardware for launch-eligible teams.

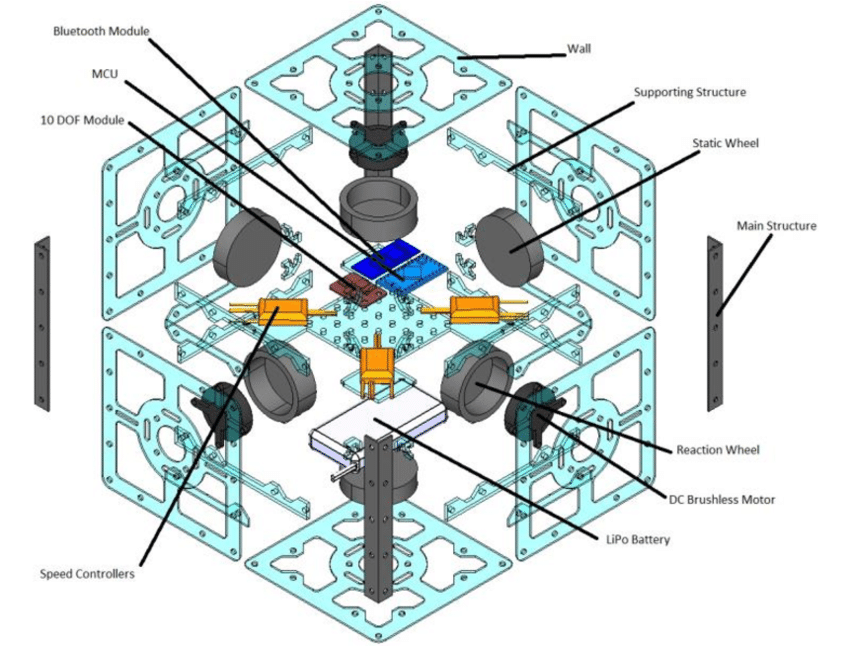

The Low-Cost Hardware Kit: Components for Hands-On Assembly

Each student receives a complete kit to build their mock satellite, fostering individual experimentation before team integration. Here’s what it includes:

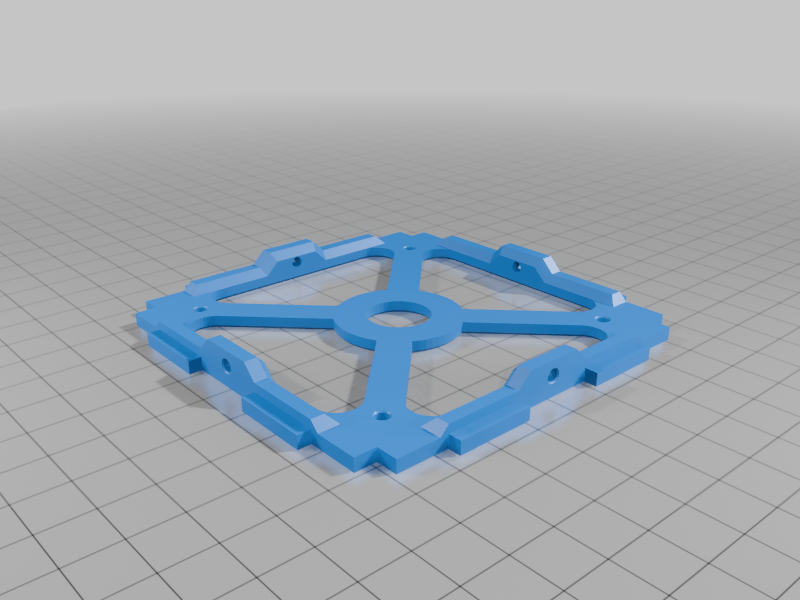

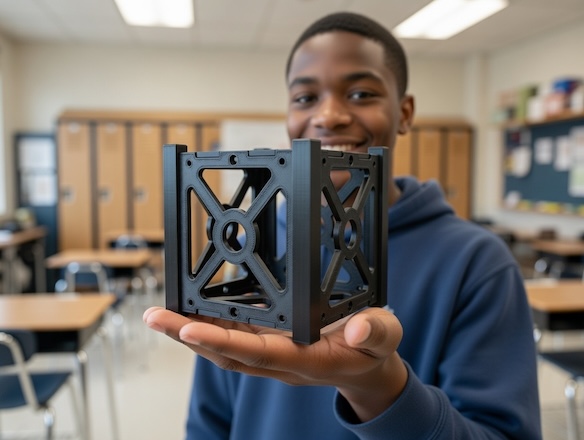

- 3D Printed Frame (10x10x10 cm): A lightweight PLA or ABS plastic chassis, printable on standard desktop 3D printers like the Ender 3. It provides structural integrity and mounting points for all internals, costing about $5-10 in filament.

- Low-Power Raspberry Pi (e.g., Pi Zero W): The “brain” of the satellite, handling computation, data processing, and control. At ~$10-15, it’s energy-efficient and supports Python programming for simulations.

- Solar Panel (Small Photovoltaic Cell): A 5V/2W panel (~$10) to demonstrate energy harvesting, connected to charge the battery and power the system during “daylight” tests.

- Rechargeable Battery (e.g., LiPo 3.7V 500mAh): Provides backup power for “eclipse” scenarios, teaching energy management (~$5-8).

- 3-Axis Orientation Sensor (IMU like MPU-6050): An accelerometer/gyroscope module (~$3-5) to detect tilt, rotation, and acceleration, essential for attitude control simulations.

- Camera Module (e.g., Raspberry Pi Camera V2): A compact 8MP sensor (~$25) for mock Earth imaging, star tracking or environmental monitoring, introducing data capture.

- GPS Module (e.g., NEO-6M): A low-cost receiver (~$15-20) for simulated positioning, helping students understand orbital tracking.

- 3 Reaction Wheels (Small DC Motors with Flywheels): Custom low-cost setups using hobby motors and 3D-printed wheels (~$10-15 total), to practice torque-based orientation control.

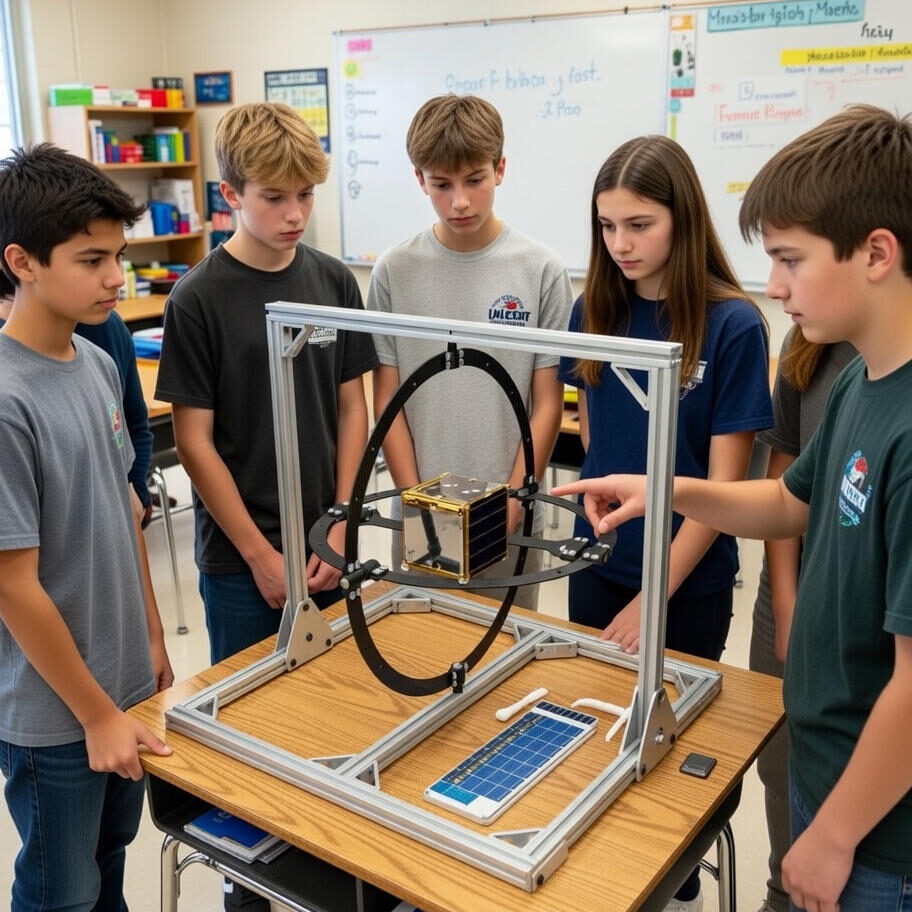

- 3D Gimbal Simulator: A DIY ball-bearing frame (~$30-50). This larger enclosure fits the entire mock satellite, allowing free rotation on all three axes to mimic microgravity and test reaction wheels without actual space conditions.

These components are sourced from reliable vendors, ensuring safety and ease of assembly with basic tools like screwdrivers and soldering irons. The total kit cost stays low by leveraging open-source designs from projects like the GitHub 1U CubeSat prototype.

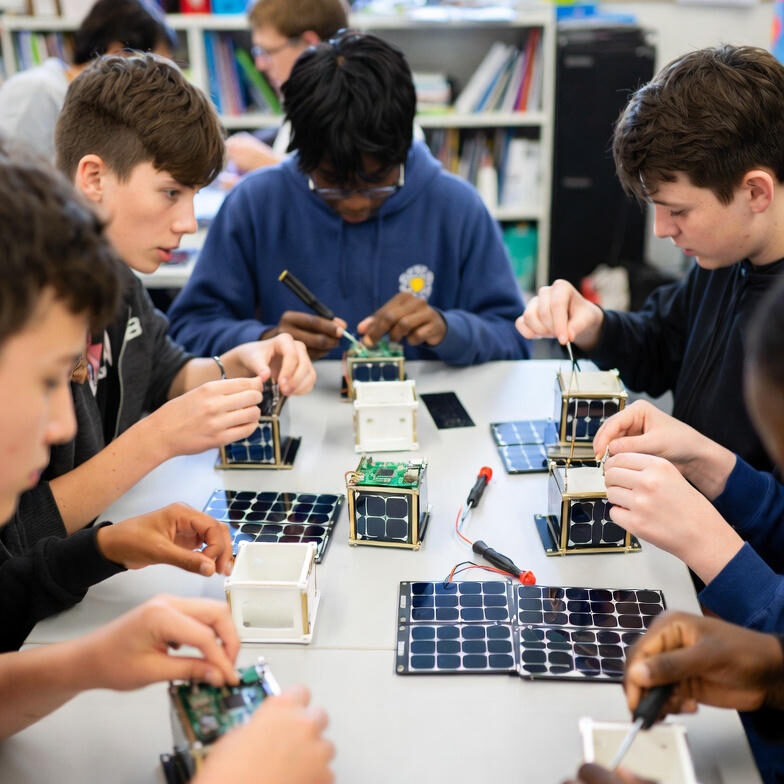

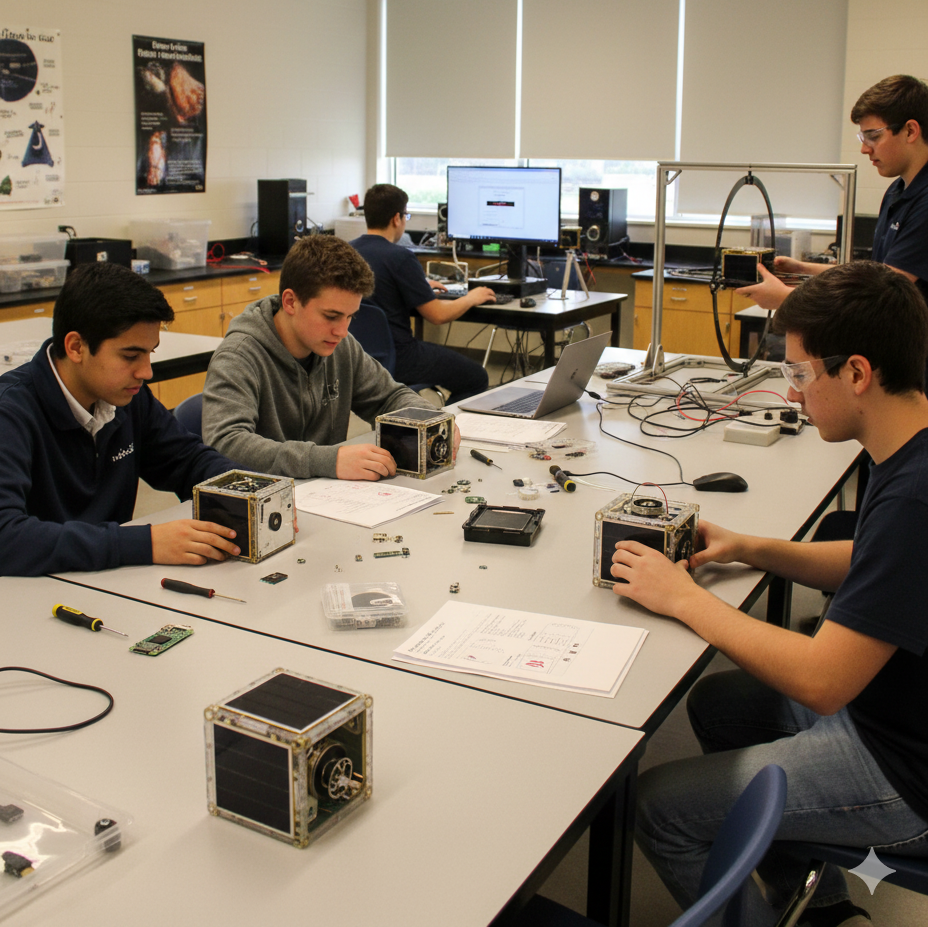

Assembly Process and Lessons Learned

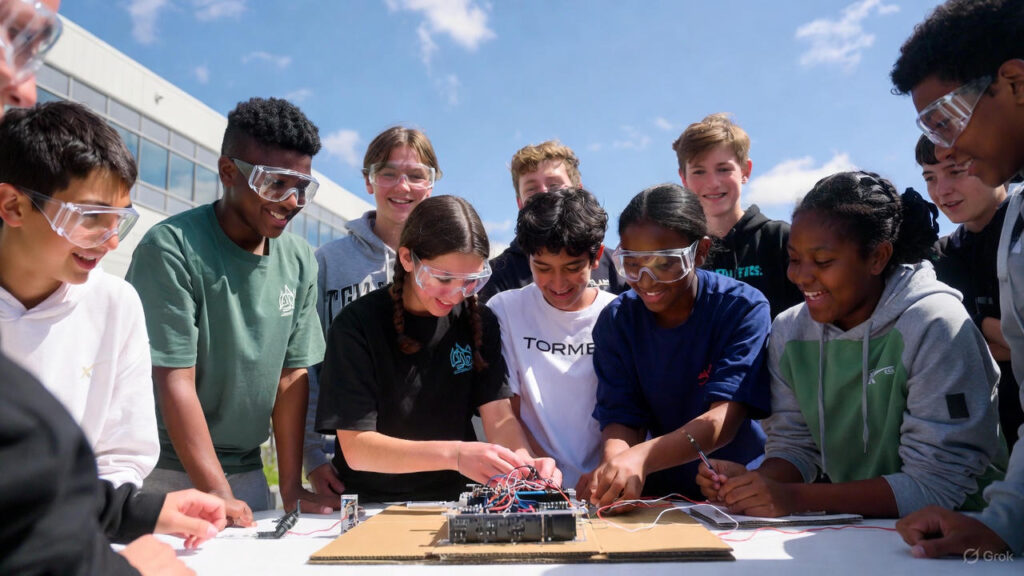

Assembly is a guided, step-by-step process over several workshop sessions, starting with the frame and progressing to integration. Students begin by printing and assembling the frame, then mount the Raspberry Pi and connect peripherals via GPIO pins. Wiring the solar panel and battery teaches circuit basics, while integrating the IMU, camera, GPS, and reaction wheels involves coding simple scripts for data logging and control loops. The gimbal setup comes last: Students place the completed mock-up inside the ball-bearing-mounted cradle, programming the reaction wheels to stabilize orientation during manual “disturbances.”

Key lessons emerge during this hands-on phase:

- Integration Challenges: Students learn that components must work in harmony—e.g., mismatched power draws can drain the battery quickly, emphasizing efficiency and testing.

- Debugging and Iteration: Common issues like loose connections or sensor calibration errors teach troubleshooting, resilience, and the iterative nature of engineering.

- Team Collaboration: Sharing kits encourages division of labor (e.g., one handles hardware, another codes), mirroring real space missions and building soft skills.

- Safety and Precision: Handling electronics introduces ESD precautions and precise soldering, instilling professional habits early.

By the end, students have a working mock-up that can “orient” itself on the gimbal, capture images, and log GPS/IMU data—proving concepts like orbital mechanics in a tangible way.

Scaling to Space-Worthy Hardware: Advanced Team Components

For teams advancing to potential launches (via SpaceX rideshare if funded), we upgrade to space-qualified equivalents shared across the group. These aren’t in individual kits but used for the final prototype, ensuring compliance with NASA/FCC standards.

- Frame: Switches to aluminum 6061-T651 or 7075 alloys (~$50-100) for superior strength and thermal stability, versus plastic’s vulnerability to outgassing in vacuum.

- Raspberry Pi Equivalent: Radiation-hardened single-board computers like space-grade ARM processors (~$200+), tested for total ionizing dose (TID) resistance up to 100 krad, unlike commercial Pis that fail in radiation.

- Solar Panels: Space-rated triple-junction cells (~$100-200) with high efficiency (30%+) and radiation tolerance, compared to commercial panels’ degradation in space.

- Battery: Aerospace lithium-ion packs (~$150) with thermal runaway protection and vacuum-sealed casings, versus hobby LiPos that could leak or explode.

- IMU/Sensors: Rad-hardened versions like Honeywell HG4930 (~$500+), certified for -55°C to +125°C and vibration up to 20g, far beyond commercial limits.

- Camera/GPS: Space-qualified modules (e.g., from Pumpkin or AAC Clyde Space, ~$300-500 each) with shielded electronics and low-outgassing lenses.

- Reaction Wheels: Precision units like the Maryland Aerospace MAI-400 (~$1,000-2,000 for a set), with vacuum-lubricated bearings and torque accuracy, versus hobby motors’ inefficiency and wear.

No gimbal for space—actual launches rely on orbital dynamics.

Key Differences: Space hardware prioritizes radiation hardening (e.g., shielded chips to prevent single-event upsets), vacuum compatibility (no outgassing materials to avoid contamination), thermal resistance (wide temperature ranges without failure), and mechanical toughness (vibration/shock testing per MIL-STD-810). Commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) parts are cheaper but untested for space, risking mission failure—space-qualified versions undergo rigorous screening, increasing costs 5-10x but ensuring reliability. This progression from mock-ups to flight-ready builds keeps the program feasible and scalable, proving your non-profit idea’s potential for real impact.

Ready to join? Apply now and help us fund these kits—your support turns student dreams into orbital realities!